Vol. 27 - Num. 107

Original Papers

Community health promotion through the implementation of the “Taking care of your child's health” programme

Ana Martín Gerechtera, Marta Esther Vázquez Fernándeza

aPediatra. CS Circunvalación. Gerencia de Atención Primaria de Valladolid Este. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

Correspondence: A Martín. E-mail: a.martingere@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Martín Gerechter A, Vázquez Fernández ME. Community health promotion through the implementation of the “Taking care of your child's health” programme . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:245-57. https://doi.org/10.60147/6fbb2c2e

Published in Internet: 03-09-2025 - Visits: 4235

Abstract

In response to the need of several families to resolve doubts about parenting and issues related to their children's health, a pediatric primary care team took the initiative to develop this community-based activity. The four workshops offer training in the prevention and identification of childhood diseases, knowledge about neurodevelopment, nutrition, infections and the use of screens, as well as skills to act in emergencies. In short, creating spaces where concerns can be addressed and a social support network formed, especially for first-time parents. The study highlights the importance of health prevention and promotion, showing that learning through these activities is possible and necessary, improving the relationships between families and providers, encouraging healthy habits, and increasing knowledge of pediatric health in the household.

Keywords

● Education ● Health ● Prevention ● Promotion ● WorkshopsINTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) underscores that health education is a strategy whose aim is to improve outcomes and reduce inequities in health.1 Several studies2 have demonstrated that health education contributes to improving the management of common diseases and reduces the burden on health care systems. These initiatives help bring knowledge to the population, promoting healthier lifestyles and providing families, especially the most underprivileged in terms of social determinants of health (SDHs),3 of self-care tools and skills. The aim is not just the dissemination of information, but also skill acquisition and health literacy.4,5

In this context, we have developed a project called “Taking Care of Your Child’s Health,” aimed especially at pregnant women and families during the first three years of life. The topics that it covers (child care, developmental milestones, common skin injuries, nutrition, obesity prevention, early and excessive screen use, fever and respiratory infections and first aid) address the most frequent concerns of caregivers in the early years of life.6 The specific objectives are:

- Helping families resolve the doubts that arise in raising their children.

- Describing and carrying out the activities included in this community-based activity.

- Assessing the epidemiological and sociocultural factors that influence the interest of the population in the activity.

- Assessing the overall level of satisfaction of the families that participate in the activity.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of the health promotion activity by analyzing knowledge before and after attendance.

- Analyzing the experience with the activity and creating a model that can be exported to other health care areas.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Target population

- Inclusion criteria: pregnant women and families with children aged less than 3 years in the province of Valladolid.

- Exclusion criteria: language barrier, except when an interpreter was available.

Participant recruitment

The activity was promoted by the nurses, midwives and pediatricians of the two health care areas of Valladolid during prenatal care visits and routine child check-ups in the primary care center. It was advertised by placing posters in primary care centers and civic centers, through institutional social networks (Sacyl [Health Care System of Castilla y León], APAPCYL [Association of Primary Care Pediatrics of Castilla y León], AEPap [Spanish Association of Primary Care Pediatrics]) and mass media (local TV, radio and press).

Study sample

Previously informed families filled out a form accessed via QR code. This form covered the registration and informed consent and asked whether the individual that completed it would bring someone else. Between 25-30 people were allowed to register per workshop. If the workshop was full, they were offered participation in the next one.

Coordinating team and facilitators

After the coordinating team, formed by pediatricians, developed the activities and designed the study,6 a multidisciplinary working group was created to facilitate the workshops: pediatric nurses, pediatricians, family and community physicians, medical and nursing inter-residents in pediatrics (MIR, NIR), medical and nursing students. Each workshop had two facilitators, one an educator and the other an observer that collected data on attendance and participated in group interactions.

Setting and schedule

The activity was carried out in the civic centers of each health care area, thus covering the entire province of Valladolid; according to the Spanish Tax Agency, the economic differences between these two areas7,8 amounts to a 47.07% difference in resources based on the percentage difference in the mean net income.

Workshops were held once a week, alternating between areas. They were held from May 2024 to March 2025 in the afternoon, from 5:30 pm to 7 pm.

Scope of the program

The activity has been endorsed by the Ministry of Health as a health care resource and it is included in the LOCALIZA SALUD resource map. The project was launched in one health care area first and then in the other. Recently, the activity started to be offered in risk, vulnerable populations (Moroccan immigrants, with the help of an interpreter and questionnaires translated to Arabic, the Romani population and in a public nursery).

Educational intervention

The activity consisted in the delivery of four workshops:

- General care: is what is happening to my child normal?

- Nutrition and prevention of childhood obesity.

- Fever and respiratory infections.

- First aid in emergencies.

The workshops (Table 1) were designed with group-based, participatory community health improvement process (CHIP) and health education (HE) methodology based on an active learning approach.9 At the end of each workshop, the facilitators answered questions and knowledge was consolidated, with participants sharing what they had learned and what they had most liked.

| Table 1. Structure of the delivered workshops (content, techniques and duration) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Workshop 1. General care | Technique | Duration (minutes) |

| 1. Presentation of the workshop and ground rules. | Brainstorming. Filling in form (QR code) assessing prior knowledge | 5 |

| 2. Expectations and fears related to parenthood | Brainstorming (Mentimeter app) | 10 |

| 3. What are the basics of newborn care? | Phillips 66/presentation | 10 |

| 4. What is normal and what is abnormal? | Photographs shown. Families assess severity using colored cards. Discussion | 20 |

| 5. Neurodevelopment: warning signs | Classroom investigation. Developmental milestones, red flags that should prompt alarm. Impact of technology on children. Responses with commentary | 20 |

| 6. Recommended digital resources | Presentation of resources. Q&A | 15 |

| 7. Evaluation | Evaluation round. Satisfaction survey. Post-workshop knowledge assessment form | 10 |

| Workshop 2. Nutrition and prevention of childhood obesity | Technique | Duration (minutes) |

| 1. Presentation of the workshop and ground rules. | Presentation. Brainstorming. Previous knowledge form | 5 |

| Presentation | ||

| 2. Healthy/unhealthy eating. “What did you eat yesterday?” | Discussion | 15 |

| 3. Advantages and disadvantages of healthy eating | Grid | 10 |

| 4. Label reading and healthy shopping | Practice and video 'Affordable and healthy food'. | 15 |

| 5. Quiz game | Online trivia quiz (Kahoot) | 15 |

| 6. Sedentary behavior and screens | Brainstorming. Parental control skills | 20 |

| 7. Evaluation | Evaluation round/satisfaction survey. Post-workshop knowledge form | 10 |

| Workshop 3. Fever and respiratory infections | Technique | Duration (minutes) |

| 1. Presentation of the workshop and ground rules | Brainstorming. Prior knowledge form | 5 |

| Presentation. Differentiation of upper respiratory tract infections: viral/bacterial; flu/pharyngitis/otitis… | ||

| 2. Experiences with children with fever. What did participants feel? What did they do? Were there any problems? | Brainstorming | 10 |

| 3. Grid puzzle and 10 Rules of Cough and Fever26 | Investigation/analysis. Handout: puzzle grid showing situations and possible solutions (true/false/I don’t know) to work on in small groups | 20 |

| 4. Practice scenarios: What to do if…? | Skill building | 30 |

| Presentation | ||

| 5. Nasal irrigation and temperature measurement | Video on nasal irrigation | 20 |

| Role play | ||

| 6. Evaluation (activity 7) | Evaluation round/satisfaction survey. Post-workshop knowledge form | 5 |

| Workshop 4. First aid | Technique | Duration (minutes) |

| 1. Presentation of the workshop and ground rules | Brainstorming. Prior knowledge form | 5 |

| 2. Theory of first aid in emergency situations. | Presentation | 25 |

| 3. Practice | Skills. Practice with simulators in small groups. Choking, safety position, adult and pediatric CPR, seizures, asthma exacerbations and diabetic attacks27 | 50 |

| 4. Evaluation (activity 4) | Evaluation round/satisfaction survey. Post-workshop knowledge form | 10 |

Sample size calculation

The minimum sample size for the estimation of a population proportion was calculated with the GRANMO online calculator version 7.12. A sample of at least 61 participants (for a 95% level of confidence, a a value of 0.05 and a power greater than 0.8 in a two-tailed test), with an expected improvement of 0.7 to 0.9%.

Study design

Prospective, observational and descriptive study based on the experience acquired through the implementation of the “Taking care of your child's health” program.

Study variables

We collected anonymous data on the attendance and epidemiological characteristics of participants (sex, age, number of children, educational attainment) and used ad hoc forms to assess knowledge and satisfaction for each of the workshops. In each workshop, the same form was used for assessment of knowledge before and after the session (Table 2). The aim of the analysis was to determine whether there was a significant increase in knowledge after the workshops.

| Table 2. Questions and percentage of correct answers before and after training | ||

|---|---|---|

| General care questions (True/False/ Don't know) | Correct answers (%) | |

| Before | After | |

| Newborn and infant care is primarily the mother's responsibility | 90.6% | 96% |

| The stump should be treated with alcohol | 100% | 96% |

| If the baby cries less than 3 hours after feeding it is because the milk supply is insufficient | 93.8% | 96% |

| The feeding schedule must be set as soon as possible for the baby to feed regularly and learn | 61.1% | 78.6% |

| One cannot get pregnant while breastfeeding | 100% | 100% |

| Spreading honey or sugar on the pacifier helps soothe the baby | 94.4% | 100% |

| If you have mastitis (inflammation of the mammary gland) you should discontinue breastfeeding | 78.1% | 92% |

| No medication can be taken while breastfeeding | 96.9% | 100% |

| Most childhood skin rashes are benign and usually disappear on their own | 77.8% | 87.5% |

| Neurological development is complete from birth onwards | 85.7% | 100% |

| If the child does not babble at 6 months or does not respond with sounds when you talk to him/her, I should be concerned | 71.4% | 38.5% |

| When is it normal for the baby to be able to sit up? Before 6 months of age / From 6 to 9 months of age / After 9 months of age |

100% | 100% |

| Screen use causes language delay and increases attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms | 100% | 100% |

| Until what age do you think your child should not use screens (TV, cell phones, tablet)? Before 2 years/Before 6 years/Before 12 years/I don't know |

7.1% | 30.8% |

| Questions about feeding/nutrition (True/False) | Correct answers (%) | |

| Before | After | |

| The concepts of feeding and nutrition are the same | 86.5% | 96.3% |

| Children should eat when they feel like it, without regular schedules. | 62.2% | 85.2% |

| Eating with the TV, tablet or smartphone on helps to get children to eat everything and faster | 91.9% | 96.2% |

| Vegetarian diets carry an increased risk of iron deficiency anemia | 40.5% | 48.2% |

| No fats of any kind should be eaten. They are harmful to health | 91.9% | 100% |

| Labels can help us choose healthy foods | 86.5% | 96.3% |

| Processed and ultra-processed foods are the same thing | 89.2% | 85.2% |

| Doing some physical activity improves current and future health | 97.3% | 100% |

| Questions about fever/respiratory infections (True/False/I don't know) | Correct answers (%) | |

| Before | After | |

| The temperature in fever tells us about the severity of the infection | 19.1% | 75.6% |

| Ibuprofen or paracetamol should be given whenever the child has a fever | 64.3% | 82.9% |

| In some predisposed children, fever can trigger seizures | 85.5% | 95.1% |

| Attempts should be made to lower the temperature with alcohol rubs and cold water baths | 57.1% | 87.8% |

| Colds do not cause fever | 45.2% | 41.5% |

| Any respiratory infection can be serious and requires prompt assessment by a doctor | 34.2% | 82.9% |

| Coughing helps clear mucus from the airways | 73.17% | 100% |

| Effective medications for cough and nasal discharge are available for all ages | 33.3% | 78.1% |

| Respiratory infections resolve faster with antibiotics | 52.5% | 90.2% |

| Questions on first aid and emergencies | Correct answers (%) | |

| Before | After | |

| Do you consider first aid training important? | 100% | 100% |

| Have you ever witnessed a situation where first aid was necessary? Answer: Yes |

35.62% | 100% |

| The ‘PAS’ mnemonic stands for: Peligro, Ayuda, Salvar [danger, help, rescue]/Proteger, Avisar, Socorrer [protect, warn, aid]/Peligro, Avisar, Salvar [danger, warn, rescue]/I don't know |

87.67% | 100% |

| Do you know the recovery position and how to perform it? Answer: Yes |

64.38% | 100% |

| How would you recognize if an unconscious person is breathing or not? By observing if their chest rises and falls/Simply by listening/Observing, hearing and feeling whether they are breathing |

87.93% | 93.75% |

| If someone remains motionless on the ground after a sudden fall, what should we do if they are not responding to stimuli, but are breathing well? Try to lift or sit them up to see if they respond to stimuli/Put them on their back to breathe better/Put them in a lateral recovery position, call an ambulance and check that they are still breathing/Perform chest compressions |

100% | 100% |

| How many compressions and breaths should be delivered to an adult in cardiorespiratory arrest? 15 compressions and 2 breaths/30 compressions and 2 breaths/30 compressions |

64.81% | 100% |

| When a person is choking and coughing, the recommendation is to: Give back blows/Try to remove the object with our fingers/Encourage them to cough forcefully, refraining from doing any of the above actions |

80.82% | 95.56% |

| What would you do in the case of a choking person losing consciousness? Give back blows/Initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation/Perform the Heimlich maneuver |

53.06% | 71.43% |

| A person experiencing an anaphylactic allergic reaction should be given adrenaline. Adrenaline should only be administered by health care professionals | 47.95% | 91.30% |

| Diabetics receiving insulin treatment can eat any type of food | 73.97% | 71.11% |

Forty-two questions were included: 14 questions from the first workshop, 8 from the second, 9 from the third, and 11 from the fourth. There were also 5 questions about the content, usefulness and structure of the workshop, and an open-ended question about the topics that most interested participants and inviting them to offer suggestions.

Statistical analysis

An Excel spreadsheet was created to collect the data. We calculated means with confidence intervals (CIs), standard deviations (SDs), medians (with CIs), ranges, standard errors, coefficients of variation (CVs) and frequencies for the pre- and post-test results.

We used Excel Microsoft 365 and artificial intelligence (ChatGPT). The mean percentages of correct answers were compared with the Student t test for independent samples after assessing normality, and variances were compared with the Snedecor F test. Values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the corresponding health care area and supported by the Research Support Unit of the Eastern Area of Valladolid.

RESULTS

Attendance

Four series of workshops have been conducted in one of the health care areas, and two series in the other. This study encompasses the last two series in each health care area. A total of 184 individuals registered voluntarily and provided informed consent (Table 3), exceeding expected attendance. The mean number of participants in each workshop was 12.27 (SD 5.67 participants). There was a predominance of female participants (71.73%; CI 71.45 to 72]). Couples amounted to 80% of the total participants.

| Table 3. Quantitative summary of study participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop | Average number of attendees per workshop | Area | Month | Attendees per month and workshop |

| WS1 | 10.67 | EAST | October | 7 |

| January | 11 | |||

| WEST | October | - | ||

| January | 14 | |||

| WS2 | 9.25 | EAST | October | 4 |

| January | 5 | |||

| WEST | October | 10 | ||

| January | 18 | |||

| WS3 | 10.5 | EAST | October | 5 |

| March | 10 | |||

| WEST | October | 15 | ||

| March | 12 | |||

| WS4 | 18.25 | EAST | October | 14 |

| March | 20 | |||

| WEST | October | 23 | ||

| March | 16 | |||

| Total attendees/responses | 184 | |||

| Overall mean | 12.27 (DE 5.66) | |||

More than 80% of participants were first-time parents and older than 30 years. There were only slight differences in the sex and age distribution of participants between the two health care areas. As regards educational attainment, in the Eastern Area, 6.58% of participants had completed compulsory education, 28.95% vocational education and 64.47% university degrees, compared to 2.7%, 24% and 72.2%, respectively, of participants in the Western Area (Tables 4 and 5).

| Table 4. Demographic characteristics of participants by area (slight percentage in percentage of non-response) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAST | WEST | ||||||

| Sex | Age | Education | No. Children | Sex | Age | Education | No. Children |

| Female | 20-30 years | Compulsory education | 1 child | Female | 20-30 years | Compulsory education | 1 child |

| 70.83% | 11.84% | 6.58% | 88.16% | 73.15% | 11.11% | 2.78% | 80.56% |

| Male | More than 30 years | Vocational education | 2 or more children | Male | More than 30 years | Vocational education | 2 or more children |

| 31.94% | 88.16% | 28.95% | 9.21% | 26.85% | 87.96% | 24.07% | 12.04% |

| University | University | ||||||

| 64.47% | 72.22% | ||||||

| Table 5. Demographic characteristics of overall sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | ||||

| Sex | Age | Education | No. Children | |

| Female | 20-30 years | Compulsory education | 1 child | |

| 71.74% | 11.41% | 4.35% | 83.70% | |

| Male | More than 30 years | Vocational education degree | 2 children | |

| 28.26% | 88.04% | 26.09% | 10.87% | |

| University degree | ||||

| 69.02% | ||||

Knowledge before and after the activity

Although there was improvement in some questions while others remained unchanged, there was overall improvement in participant knowledge in all workshops (Table 6).

| Table 6. Percentage of correct answers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of hits table | WS1 | WS2 | WS3 | WS4 |

| Before | 82.64% | 80.74% | 51.26% | 69.62% |

| After | 86.81% | 88.41% | 81.57% | 92.32% |

| Difference (% improvement) | 4.166% | 7.666% | 30.308% | 22.694% |

The least improvement corresponded to the first workshop on general child care, followed by the nutrition workshop. The most improvement corresponded to the workshop on respiratory infections: participants answered 51.26% of the questions correctly (CI 37.08 to 55.4) before the workshop and 81.57% (CI 69.83 to 93.3) after the workshop. The difference amounted to 30.30%. The second workshop with the most improvement was the one on first aid, where the percentage of correct answers increased from 69.2% (CI 52.7 to 82.15) at baseline to 92.32% (CI 85.17 to 99.45) after the workshop.

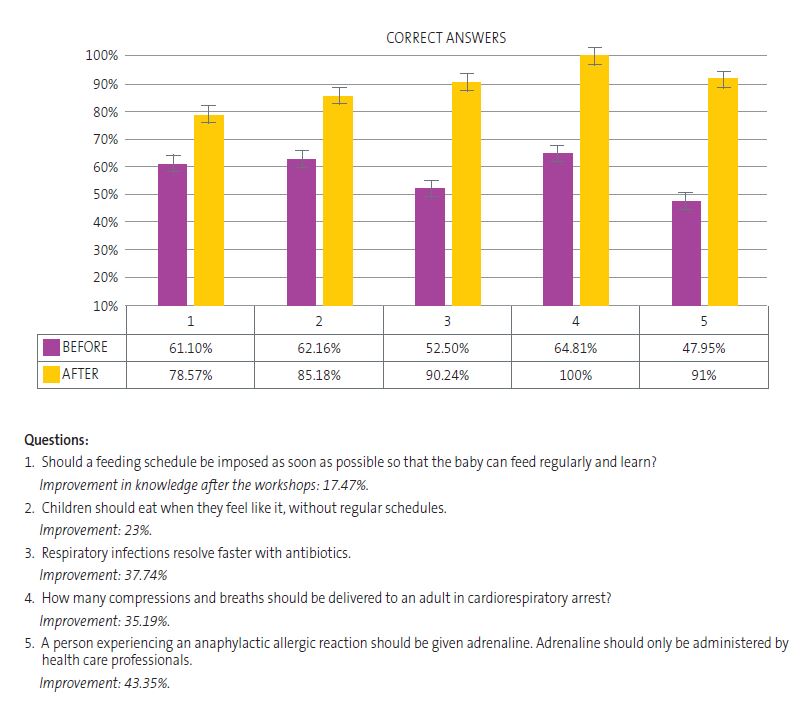

Overall, the workshops achieved a difference in knowledge of 16.2% (p <0.05). Figure 1 shows the items with the most relevant improvement.

Analysis of knowledge by health care area

In the Eastern Area, there was a 16.10% improvement between the pre- and post-questions (CI 6.2 to 26). The biggest difference corresponded to the third workshop, on fever and respiratory infections, with a 27.89% improvement. In the Western Area, there was an improvement of 15.22% (CI 1.28 to 29.5), with the first aid workshop standing out with an improvement of 26.98% compared to 11.50% in the Eastern Area. Overall, the differences between the Eastern and Western Areas were small and therefore not significant.

With regard to prior knowledge, the baseline was higher in the Western Area compared to the Eastern Area (5.28%). The percentage of correct answers after the workshops in the Western Area was higher for the first three workshops, exceeding 10%. The only workshop where participants in the Eastern Area demonstrated greater prior knowledge was the first aid workshop.

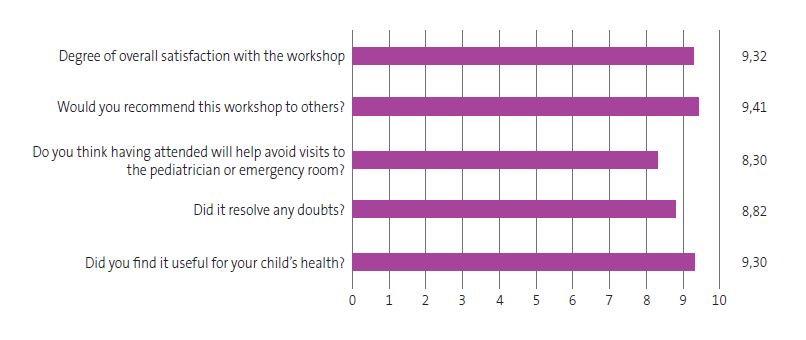

Satisfaction survey

Participants rated their satisfaction with the workshops with an overall score of 9 out of 10, with a 95% CI of 8.91 to 9.14 and little dispersion (SD 1.57) (Figure 2). The workshop that received the least positive responses was the one on nutrition and obesity, with a mean satisfaction rating of 8.16 (SD 2.16). The workshop that received the most positive responses was the one on fever and infections. There were no significant differences between the different workshops.

The open question revealed an interest in learning more about breastfeeding, the delivery of presentations, continuing the activity and offering some online sessions.

Results and community impact

The project was covered in the mass media and local social networks,10-14 including the Asociación de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de Castilla y León (Association of Primary Care Pediatrics of Castilla y León).15

DISCUSSION

Despite the limitations inherent to this type of study, which we discuss at the end of this section, many primary care community-based activities16 have proven to be effective for promotion of healthy lifestyles and prevention of disease. A study of a HE program named If it’s urgent for you, is it urgent for me? in our health district, published in 2020,17 showed that a HE program that targets families can reduce the frequency of pediatric care visits and improve their appropriateness compared to a control group of families that did not participate in the intervention.

Our study, Taking care of your child’s health, also assessed the effectiveness of such a community-based activity aimed at families to modify lifestyle habits that, from preconception through the end of early childhood, can have an impact on children’s health and their adult lives. We found an overall improvement in knowledge of more than 16% (p <0.005); as for the incorrect answers at baseline, 75.8% were answered correctly after the educational activity. This suggest that workshops were effective in expanding and improving the previous knowledge of participants. In addition, excluding the questions for which there was no improvement (because they had obvious answers) and “negative” improvement (bias due to participant noncompliance or escalating commitment on answering), this result improves by more than 20%.

The first aid workshop generated the most interest and attendance, while the workshop on fever and respiratory infections achieved the greatest improvement in knowledge. The fact that most participants learned how to follow an emergency algorithm, contact health services and perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), first aid for choking and other emergency procedures in adults and infants was encouraging. There was less variation in the first and second workshops, which can probably be attributed to the simplicity of the questions and the greater prior knowledge of the participants. This information can guide future iterations, adjusting strategies and prioritizing workshops with the greatest educational impact.

On the other hand, this study analyzed differences between two health areas in the same province. Overall, we observed a higher level of baseline knowledge and greater attendance in one of the areas, possibly due to, among other factors, more aggressive recruitment, a greater number of children or a higher educational attainment. Several studies support the notion that health knowledge is affected by other health determinants, such as the geographical location of the home and socioeconomic status.18 According to various sources,9,20 there is a positive or negative association with health literacy and general knowledge based on these factors.21 We conducted a search for the two areas to analyze whether there was a correlation between such findings and the results of our study. All of the above factors may have a cumulative effect on families' knowledge and their care. However, our study did not find evidence that they had a significant impact on knowledge before and after the educational activity (there were small differences between the areas, but they were not significant).

The study suggests that the activity mainly attracts people with higher educational attainment and health education levels, which was reflected by the greater attendance in the Western Area (which had 5.24% more participants who had received health education before compared to the Eastern Area). It is possible that advertising the activity through social media and local mass media is more likely to reach families with greater digital literacy, which can be a source of selection bias toward individuals with medium to high educational attainment. Therefore, we propose actively recruiting people from lower socioeconomic levels and culturally diverse. At this time, the nutrition workshop has been adapted for the Romani population and the baby care workshop for the Moroccan population, both of which have been positively received, with good subjective satisfaction ratings (not included in the study due the small sample sizes).

The reported satisfaction was very high: 9 out of 10. The workshop that attracted the most interest was the one on fever and respiratory infections. There was clear unanimity in the positive satisfaction ratings for this project, very similar to the satisfaction ratings of other studies on health promotion at the primary care level.22-24

Finally, it should be noted that there are limitations to the study; the short time elapsed from the training to the evaluation is one of its main limits, and it would be useful to supplement it with a later evaluation.

Another challenge is that some families sign up but do not attend due to forgetfulness, lack of time, access problems, information found on the Internet or reliance on medical visits. To fit the intervention to the target population as much as possible, we sent reminders, offered afternoon hours and allowed participants to bring young children. For Moroccan and Romani families, morning sessions were offered to adapt to their lifestyles. In future workshops, it will be important to monitor absenteeism, listen to the topics participants want to discuss, encourage them to attend and adapt to their needs. We also need to consider the suggestions of some families to combine face-to-face and online sessions with digital materials.

From the perspective of prevention, epidemiology, and the dissemination of medical and health concepts, this study attempts to reflect the usefulness of proactive medicine, reaching out to the community and responding to identified health needs. We found a statistically significant improvement in the immediate responses after the intervention, and participants expressed their appreciation, both through questionnaires and in person, for having learned useful health-related knowledge and skills for child-rearing.25 This supports the importance of health promotion, especially among the caregivers of infants and children, and underscores the need to assess its impact on lifestyle habits, preventable diseases and demand of health care resources by following up on the project.

CONCLUSIONS

- Although attendance depends on several factors, a more proactive approach is needed to engage families, especially those that are most vulnerable in terms of social determinants of health, to improve participation and deliver accessible health education.

- The workshop that generated the most interest was the first aid workshop, followed by the workshop on fever and respiratory infections.

- This project was motivated by the need to respond to a health need in the community, and we found that knowledge increased by 16% after the workshops compared to baseline.

- Participants rated the experience positively, noting that it was useful and that they learned essential concepts and acquired new parenting tools.

- In order to verify long-term health outcomes, these initiatives must be extended over time and exported to other health care areas.

CONFLICTS DE INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the preparation of the published manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria · APapCyL: Asociación de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de Castilla y León · CHIP: community health improvement processes · CI: confidence interval · CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation · CV: coefficient of variation · HE: health education · MIR: medical intern-resident · NB: newborn · Sacyl: Sanidad de Castilla y León · SD: standard deviation · SDH: social determinants of health · WHO: World Health Organization.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Educación para la salud: manual sobre educación sanitaria en atención primaria de salud. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/38660

- Mosteiro Miguéns DG, Rodríguez Fernández A, Zapata Cachafeiro M, Vieito Pérez N, Represas Carrera FJ, Novío Mallón S. Community activities in primary care: a literature review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2024;15:21501319231223362. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319231223362

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Determinantes sociales de la salud. Washington D.C.: OPS/OMS; 2025 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://www.paho.org/es/temas/determinantes-sociales-salud

- Hernández-Díaz J, Paredes-Carbonell JJ, Marín Torrens R. Cómo diseñar talleres para promover la salud en grupos comunitarios. Aten Primaria. 2014;46(1):40–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2013.03.006

- Juvinyà-Canal D, Bertran-Noguer C, Suñer-Soler R. Alfabetización para la salud, más que información. Gac Sanit. 2018;32(1):8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.06.005

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Guía de acción comunitaria para ganar en salud. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad; 2021 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/entornosSaludables/local/estrategia/herramientas/docs/Guia_Accion_Comunitaria_Ganar_Salud.pdf

- Agencia Tributaria. Estadística de los declarantes del IRPF de los mayores municipios por código postal: 2022. Madrid: Agencia Estatal de Administración Tributaria; 2022 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/AEAT/Contenidos_Comunes/La_Agencia_Tributaria/Estadisticas/Publicaciones/sites/irpfCodPostal/2022/jrubik2ae7dc136b9bac0e57f31a18ba8184f49c36f6fb.html

- Agencia Tributaria. Estadística de los declarantes del IRPF de los mayores municipios por código postal: 2022. Madrid: Agencia Estatal de Administración Tributaria; 2022 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/AEAT/Contenidos_Comunes/La_Agencia_Tributaria/Estadisticas/Publicaciones/sites/irpfCodPostal/2022/jrubikf26c28cb47a6657073d8a750ca35a1a14e3f8f223.html

- Aguiló Pastrana E, Cucco M. Metodología de los procesos correctores comunitarios (metodología ProCC) [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://comunidad.semfyc.es/wp-content/uploads/Comunidad_MetodologiadelosProcesosCorrectoresComunitarios.pdf

- Cómo actuar con los niños ante una urgencia, virus respiratorios, obesidad infantil… In: El Norte de Castilla. 3 de febrero de 2025 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at www.elnortedecastilla.es/valladolid/talleres-valladolid-ninos-urgencia-fiebre-virus-respiratorios-obesidad-20250203131147-nt.html

- Atención Primaria ofrece más talleres para padres sobre el cuidado de los hijos. In: El Día de Valladolid. 1 de febrero de 2025 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at www.eldiadevalladolid.com/noticia/z8fb9789e-ae45-de53-07b33a9ff4ac9551/202502/atencion-primaria-ofrece-mas-talleres-de-pediatria-para-padres

- Ayuntamiento de Arroyo de la Encomienda. La Casa de Cultura acoge hoy el taller de educación para la salud «¿Es normal esto que le pasa a mi hijo?». X (antes Twitter). 2025 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://x.com/AytoArroyo/status/1889580157226119550

- Salud comunitaria ASVAO. Instagram. 2025 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://www.instagram.com/p/DG2mBrAsh-8/

- Ledesma I. Se reanudan los talleres del programa de educación para la salud de las áreas sanitarias de Valladolid. In: APapCyL. 2025 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://apapcyl.es/se-reanudan-los-talleres-del-programa-de-educacion-para-la-salud-de-las-areas-sanitarias-de-valladolid/

- Pediatría de AP. Talleres: cuidando la salud de tu hijo. Portal Salud Junta Castilla y León. 2025 [online] [accessed 24/09/2025]. Available at www.saludcastillayleon.es/HRHortega/en/actualidad/pediatria-ap-talleres-cuidando-salud-hijo

- Menor Rodríguez M, Aguilar Cordero M, Mur Villar N, Santana Mur C. Efectividad de las intervenciones educativas para la atención de la salud: revisión sistemática. 2017 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1727-897X2017000100011

- Vázquez Fernández ME, Sanz Almazán M, García Sanz S, Berciano Villalibre C, Alfaro González M, del Río López A. Intervención educativa en atención primaria para reducir y mejorar la adecuación de las consultas pediátricas. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2020;93:e201901003.

- Nieuwenhuis J, Kleinepier T, van Ham M. The role of exposure to neighborhood and school poverty in understanding educational attainment. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(5):872-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01394-2

- Corella Piquer D, Ordovás Muñoz JM. Relación entre el estado socioeconómico, la educación y la alimentación saludable. Mediterráneo Económico. 2015;(27):283-306 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5207080

- Chaudry A, Wimer C. Poverty is not just an indicator: the relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3):S23-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.010

- Martens PJ, Chateau DG, Burland EMJ, Finlayson GS, Smith MJ, Taylor CR, et al. The effect of neighborhood socioeconomic status on education and health outcomes for children living in social housing. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2103-13. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302133

- Díaz Sánchez MC. Valoración de la satisfacción de pacientes que acuden a talleres de educación para la salud en la unidad de hospitalización breve. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 2017 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/687171

- Vaquero Barba A, Garai Ibáñez de Elejalde B, Ruiz de Arcaute Graciano J. La importancia de las experiencias positivas y placenteras en la promoción de la actividad física orientada hacia la salud. Ágora Para Educ Física Deporte [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/23792

- Herranz BJ, Pastor VML, Garzarán AP. Satisfacción de los diferentes agentes que participan en el desarrollo de un programa municipal de deporte escolar. Alto Rendimiento. 2013;146-50 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://portaldelaciencia.uva.es/documentos/61b994d88bc05f42e937cd9e

- Cofiño Fernández R, Álvarez Muñoz B, Fernández Rodríguez S, Hernández Alba R. Promoción de la salud basada en la evidencia: ¿realmente funcionan los programas de salud comunitarios? Aten Primaria. 2005;35(9):478-83. https://doi.org/10.1157/13075472

- Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Decálogo de la fiebre. In: Familia y Salud. 2014 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at www.familiaysalud.es/recursos/decalogos-aepap/decalogo-de-la-fiebre

- Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús. Guía práctica de primeros auxilios para padres. Madrid: Hospital Niño Jesús; 2017 [online] [accessed 02/09/2025]. Available at https://somprematurs.cat/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Guia-Primeros-auxiliosHospital-Nino-Jesus-1.pdf